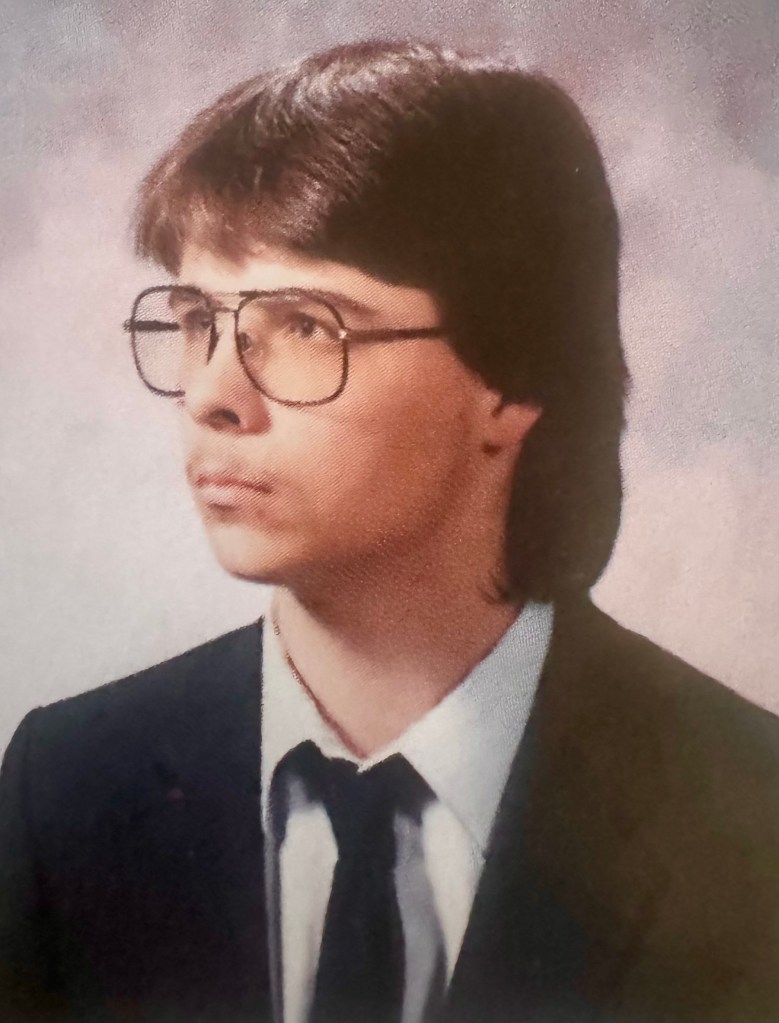

Ryan Klingensmith

As a licensed counselor, devoted husband, and proud father, Ryan Klingensmith weaves tales that explore the human condition. His fiction delves into the complexities of relationships and the resilience of the human spirit. With insight gleaned from his diverse roles, he crafts stories that resonate deeply with readers.

How did you become interested in writing?

This question is one I’m often asked at this stage of my journey, so I’d like to share some reflections on it.

One of my earliest memories of writing dates back to when I was around eight or nine years old. I vividly remember the excitement of watching “Jaws” on HBO repeatedly. Inspired by the film, I would take pieces of blank paper, fold them together, and create my own makeshift books. With pen in hand, I’d sketch scenes of a giant shark attacking people and boats, occasionally adding in snippets of dialogue from the movie or crafting my own narratives. Looking back, I see this as the starting point of my journey into writing.

During my senior year of high school, I was tasked with a memorable assignment in my English class: writing a short story. For this project, I crafted a tale centered around a cross-country muscle car race that commenced in my small hometown and culminated on a California beachfront. Aptly titled “The Great Race,” the narrative featured racing protagonists, a trusty mechanic sidekick, a romantic interest, and a sudden illness that befell one of the characters midway through the competition. True to adolescent fantasies often harbored during mundane afternoon English classes nationwide, the story concluded triumphantly with the hero saving the day, nursing the girl back to health, and clinching victory in the race. Infused with authentic slang reflective of my high school and vocational-technical auto body repair experiences, the story encapsulated the spirit of my teenage years.

I must explain that my high school memories are few, and the ones that remain are lined with cobwebs; the sharp edges of accuracy have been rubbed down to unclear boundaries of what actually happened. For many years, I held in my memory that I got the story back graded with a “C” and a verbal comment something along the lines of “nice try, next time, write it yourself.” The red pen comments on all of those demographically accurate adolescent gear-head verbiages were equally as traumatic to my perceived literary career. So, my overall impression of the first reviewed work that I had written was: good story—obviously, someone else wrote this because you couldn’t, offensive language—please adjust; people don’t want to read that filth, and I’m giving you a passing grade—so that you can graduate and get out of this school and go dig ditches for the rest of your life. I held onto that belief for many years and bumbled about with the frustration of knowing I wrote that story and not being believed that I could possibly have written it.

I recently stumbled upon that old story among my treasures from the past, which my wife fondly refers to as my hoard. As I reread the story and my teacher’s comments in red pen, it became clear to me that my teacher knew I had indeed written this story, as the comments she penned in 1989 about my writing still hold true today, according to my current editor. I struggle with sentence structuring, and tense has always been my nemesis. Old bad habits die hard, I suppose. However, one comment at the end stood out among all the others: “Your story was pretty good.” Thus, the “nice try, next time, write it yourself” remark was most likely a fabrication of my angsty teen brain for some reason. Nevertheless, the memory and drive to write a good story it created were not in vain.

Somehow, I managed to graduate high school and move forward with my life. I attended auto mechanics school and obtained an Associate’s degree in auto mechanics. However, after completing my training, I found that I no longer had the desire to work on cars. Instead, I found myself working for a mushroom mine, subcontracting for a fencing company, and eventually taking on unskilled labor for a construction company. It was during this period that my life took an unforeseen turn. Whether by the unseen blueprint of my life or a herniated disk from hauling wet cement around in a wheelbarrow for a construction company, I can’t decide which, I ended up enrolled at Penn State.

Similar to the Scarecrow at the conclusion of “The Wizard of Oz,” I discovered my brain in college. It dawned on me that I could think on a broader scale. While thinking had always been a part of my life, its depth varied depending on my level of interest. Unlike high school, in college, I had the freedom to choose classes that intrigued me—except Statistics. I had to take Statistics, and it held no allure for me. Math simply isn’t my forte. It never has been, and it never will be. You can engrave that on my tombstone.

One of the summer classes I enrolled in was a short story writing class, and it stands out as the coolest class I’ve ever taken. Even after graduate school, it remains at the top of my list. With only a handful of students due to the summer term, I biked to class on the splendid campus while living in my own apartment. The creative atmosphere was palpable. Surrounded by other creative souls, our main goal was simple: to write short stories. It was my kind of summer.

In the previous January, I began working at the local psychiatric hospital, having decided that psychology was the path for me. Over the course of six months working with teens and adults on the units, I witnessed a variety of concerning yet often intriguing behaviors. Reading through the patients’ histories to gain deeper insights, I discovered that life had not been kind to most of these individuals. So, when one of my first assignments was assigned in my short story class, I found myself with a wealth of thoughts and experiences to draw from.

The assignment had been to write a one to two-page story from the perspective of the opposite sex. Titled simply “Love,” it depicted the perspective of a sexually abused female, curled up on her bed, awaiting her abuser’s return from work. As he pulled into the driveway in his BMW, she greeted him at the door, and as he set his briefcase down, he casually asked her about dinner. The story concluded with a stark sentence: “What would you like, Daddy?” It hit hard, leaving no room for evasion, delivering blunt force trauma in just one sentence.

College is fuzzy and dusty too, not as much as high school, but I do recall receiving accolades and praise for this simple little story rooted in the histories of many of the teen girls I had worked with at the hospital. Other students in the class gave me great praise for the story, and I believe I got a good grade on it, but I don’t have a red-penned final version as proof. During my time at the hospital, I read histories and talked with patients. I couldn’t believe, and still can’t, how many people have been sexually abused. My little story brought some awareness to others about reality. I learned something with that simple story. There was an undiscussed world out there that teens were experiencing, and I exposed others to view this world. So, I’ll attribute my summer of 1994 short story class as helping me write my first story of trauma. That’s all hindsight now, viewing my writing from 30 years in the past. My ultimate goal when I was in college was to have my Klingensmith books on the shelf between King and Koontz. What a perfect last name I had.

In college, my reading list was short, primarily consisting of Stephen King and Dean Koontz. I adored their stories, and horror remained my preferred genre—then and now. Naturally, I gravitated towards writing what I loved to read. Throughout the next few years it took me to graduate, I penned chilling short stories and had them bound into booklets at Kinko’s. I relished sharing them with others. I even remember writing a story during an anthropology class when I should have been paying attention. Though anthropology intrigued me, I couldn’t resist delving into my own creative world. In my college mind, what I was writing represented my future—I was more focused on crafting the great American novel than on my textbooks. Someday, I believed, I would find myself between King and Koontz.

Crafting tales of terror proved to be challenging, far more complex than the masters made it appear. After completing a chilling tale, I would revisit it and often find it lacking. Years later, I still stand by that assessment. Horror just wasn’t my forte. While the concepts held some merit, the story progression, plot, character development, and all the essential elements fell short. Regrettably, like many writers, I eventually halted my attempts and left it to the professionals. Horror, I concluded, was best left to the likes of King and Koontz.

I persisted in my work with individuals diagnosed with mental health issues and traumatic pasts, eventually narrowing my focus to adolescents in residential placements. As I progressed, I transitioned into administrative roles within various organizations. Returning to academia, I pursued a master’s degree, furthering my expertise and assuming more significant clinical leadership responsibilities.

With this leadership came a stark realization: many professionals working with traumatized adolescents lacked a comprehensive understanding of trauma. Equally crucial to me was ensuring that the staff under my supervision comprehended the reasons behind these youths’ behaviors. While the staff exhibited empathy, true sympathy eluded them due to their disparate life experiences. This discrepancy was an undeniable reality.

My passion for writing had never truly waned. Over the years, I amassed notes, thoughts, and story ideas that could have placed me between King and Koontz, but I never made the leap to try again. However, at this point in my life, I had an epiphany—I could potentially lend a creative voice to a fictional teen that would aid mental health workers in comprehending trauma from the adolescent perspective. Thus, I embarked on the journey of penning “Quiet Room Charlee,” with Charlee serving as my fictional conduit to educate the masses about trauma.

“Quiet Room Charlee” was initially conceived as a single book. However, as I delved into the writing process, I soon realized that the entirety of the story couldn’t be contained within just one volume. Consequently, I expanded the narrative by introducing additional characters from Charlee’s life. Among them were six siblings—three boys and three girls, reminiscent of “The Brady Bunch.”

In “Quiet Room Charlee,” my aim was to maintain simplicity, momentum, and above all, to shed light on trauma in a manner that remained engaging, despite the discomfort inherent in the subject matter. Trauma, by its nature, is uncomfortable—it’s ugly, painful, and often easier to ignore. Yet, in my storytelling, I chose to confront Charlee’s trauma head-on, ensuring that it remained visible to all.

In “Quiet Room Charlee,” I drew upon my own experiences to shape his life. The struggles depicted in the story could easily parallel the experiences of innocent children in today’s world. Having witnessed the aftermath firsthand, I felt a responsibility to convey the harsh reality: child abuse remains prevalent in modern society. My guiding principle throughout was the stark acknowledgment that this is a genuine issue. If we fail to grasp the plight of these children and the traumas they endure, and neglect to educate them on breaking the cycle, then who will? Understanding their experiences is paramount to offering them the support and intervention they urgently need.

When I aspired to find my place between King and Koontz on the bookshelf, I soon realized that “Quiet Room Charlee” would belong on a different fiction shelf altogether, in a now-forgotten bookstore. Nevertheless, my narrative encapsulated a form of horror, albeit of a different kind—the raw, unfiltered horrors of reality.

“Quiet Room Charlee” found a publisher and went to print immediately, without undergoing any editing. This marked my personal first horror experience in publishing. Due to a misinterpreted email at some point along the way, the book was printed without any editing. As you can imagine, I was grammatically traumatized. Remember my earlier story about high school being fuzzy? Well, my English structure was equally fuzzy. I likely slept through every diagramming sentence class. Consequently, my mistakes were laid bare on Amazon for all to see. Fortunately, I had a few individuals who paid attention in high school English, and they graciously red-penned the book for me. With their help, I was able to produce a more readable edition. However, for those fortunate few who purchased the book as soon as it hit the online store, they received the edition with all the grammatical errors of my naivety and that misinterpreted email. My sincerest apologies to those individuals.

Those immersed in the mental health profession provided me with valuable feedback regarding the book’s portrayal of reality and its gentle instructional approach. They not only appreciated the story itself but also developed a fondness for Charlee. Bingo! I had successfully crafted a likable character whom readers were eager to follow. Additionally, colleagues in the field began using “QRC,” as it became affectionately known by one of my fans, as a teaching tool for new hires and interns in residential settings. To my knowledge, the book was even incorporated into the curriculum of introductory psychology classes at two college campuses.

“QRC” was published in May of 2008. In November of the same year, I became a father. As a result, my life became busier than ever. However, deep down, I knew that the story had to continue. Amidst juggling work, graduate school (once again), and fatherhood responsibilities, I began to pen the story of Tammee, Charlee’s sister. Her narrative burned in my mind, compelling me to bring it to life.

Tammee’s life unfolded within the confines of a Word document during the quiet hours of the night, when everyone else was asleep. Unlike the struggle of writing horror to earn a spot between King and Koontz on the bookshelf, narrating trauma came effortlessly. When people inquire about my writing process, I liken it to the experience of reading—a journey filled with unpredictability. While you may have a general idea of where the story is headed, the twists and turns unfold just as unexpectedly as when delving into a new book. It’s as simple as that.

The title of the book came easily, and Champagne Alley quickly took shape… only to sit in my computer, the cursor blinking at me, awaiting the next step: editing. My traumatic experience with editing serves as a stark example of how trauma can affect an individual. I believe Champagne Alley was completed sometime around 2009 or 2010, yet I did nothing with it due to the editing challenges.

In 2011, I became a father once again, and the experience was a whirlwind of excitement, joy, and distraction from work, much like the first time around. While being a dad remains my number one duty and will be forever, I still had Tammee’s story locked away in my jump drive. Feeling the need to share her story with the world, I turned to Facebook sometime in 2012. A connection from my distant high school days happened to know an editor. Finally, I was able to secure an editor and have the book edited. Hooray!

“Champagne Alley” delves deeper into the realms of trauma, offering another perspective on how individuals respond to adversity. While the writing process flowed smoothly, publishing posed a challenge due to the delicate nature of the trauma depicted. It prompted me to question: How much graphic detail should I share? The narrative is gritty and raw in parts, reflecting the harsh realities that arise from unfortunate circumstances. These are the consequences of bad things happening to good people, to good kids.

While writing “QRC,” I was surprised to find that some teenagers not only read the story but also connected deeply with Charlee. Originally intended for adults, I hadn’t anticipated its appeal to teens, considering it explores teenage life. Reflecting on the completion of “Champagne Alley,” I examined it from three perspectives. For professionals in the field, the portrayal of trauma from a youth perspective offered valuable insights. However, for adults outside the profession, the graphic nature of the narrative could be distressing. As for the teen audience, I felt the content was too heavy, prompting me to reluctantly edit out some of the more intense passages multiple times. I even found myself crossing out sentences in red pen during the proofing stage. Despite these edits, the book remains a weighty read, reflecting the harsh realities faced by some young people.

In 2014, “Champagne Alley” was published to widespread acclaim, receiving much positive feedback and admiration akin to “Quiet Room Charlee.” Once again, I found success in crafting a novel centered on trauma, offering readers insight into the world of a traumatized teen. The reception reaffirmed the importance of storytelling as a tool for fostering empathy and understanding among readers.

Fast forward to 2020, and the persistent editing issues in “QRC” continued to nag at me, a lingering worm in my brain. Determined to address them once and for all, I retrieved the manuscript and enlisted the expertise of a professional editor. After meticulous editing, the book was finally in polished, professional form. However, by this time, the publishing agency responsible for the initial release of “QRC” had long exited the industry. Undeterred, I resolved to take matters into my own hands and self-publish the refined version of “QRC.” Yet, I felt compelled to mark this fresh start with a new title, hence “Finding Charlee” was born. With a new cover unveiled in 2024, I reintroduced Charlee’s story to a fresh audience, eager for them to experience his journey anew. At last, I could bid farewell to the editing nightmare that had plagued me for over a decade. Welcome back, Charlee…

So, that’s the extended version of “how did you become interested in writing?” I found pleasure in crafting this piece and I trust it provides some insight into why I gravitate towards narratives that explore perceived gloom. While the stories may depict tragedy, it’s crucial to remember that children possess remarkable resilience, often more so than us adults. With compassionate and understanding adults to guide them, these young individuals have a remarkable opportunity to transcend the challenges they face and carve out a better life than the one they were initially given.

~ Ryan